Lecciones de Derecho

It’s a Privilege

Need your Illinois driver’s license back? Our attorneys handle suspensions, revocations, and hearings.

My kid wants to party all the time.

New Illinois law punishes adults who allow underage drinking, with penalties up to a felony.

Driver's License Reinstatement After a DUI Revocation in Illinois

Attorney Ramon Cervantes explains DUI revocation, restricted permits, required documents, and the SOS hearing process.

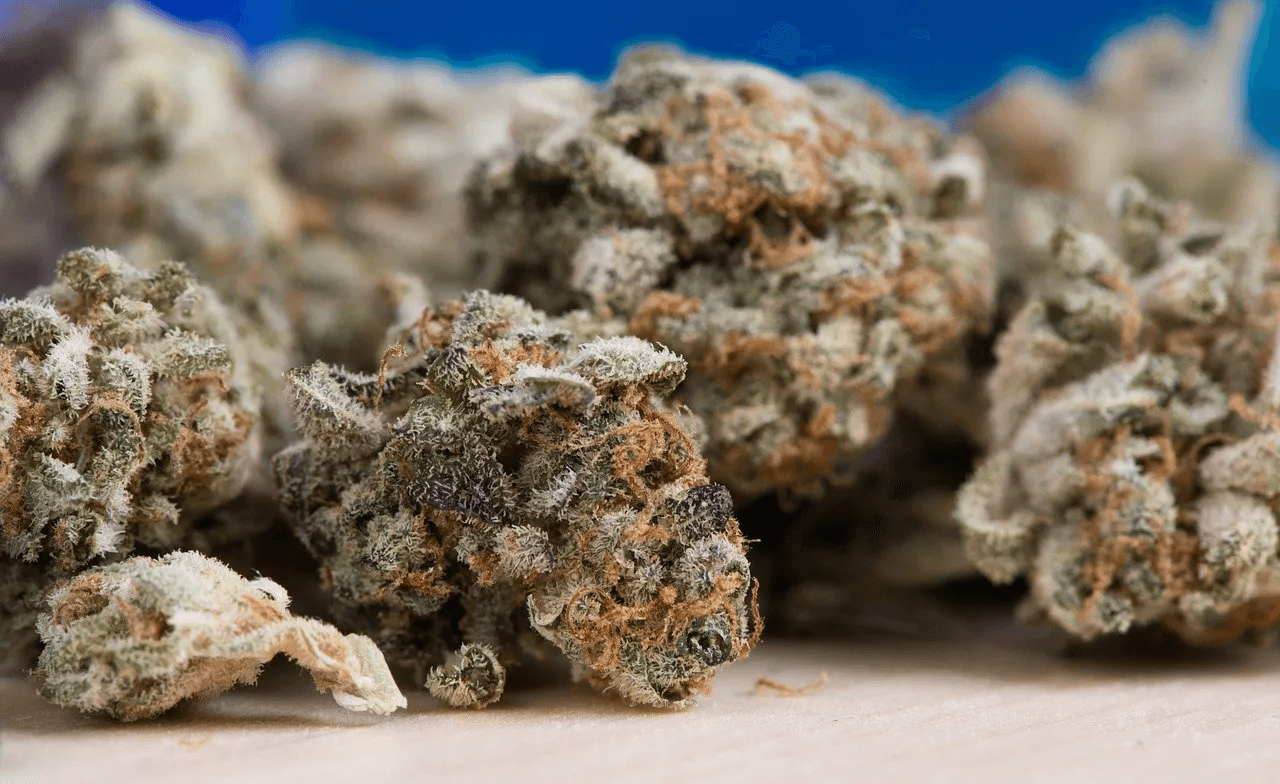

New Act Allows Cannabis Use for Pain Management

Learn how Illinois’ Opioid Alternative Pilot Program works, who qualifies, and what changes it brings to medical cannabis access.

How Work Injuries Work: Step Three

Workers’ comp claims require quick action, medical care, and legal guidance.

Fighting Drug Cases- Part 2

In drug cases, prosecutors must prove actual possession. Defense strategies can raise reasonable doubt.

Snow Falls

Illinois snow laws require clearing handicap spaces and address liability for unnatural snow or ice accumulations.

Petition To Revoke

A petition to revoke can lead to jail or harsher penalties. Know the process and why strong legal representation matters.

Deconstructing Illinois Construction Zone Laws

Learn Illinois rules for construction zones: higher fines, cell phone bans, and stricter speed laws.

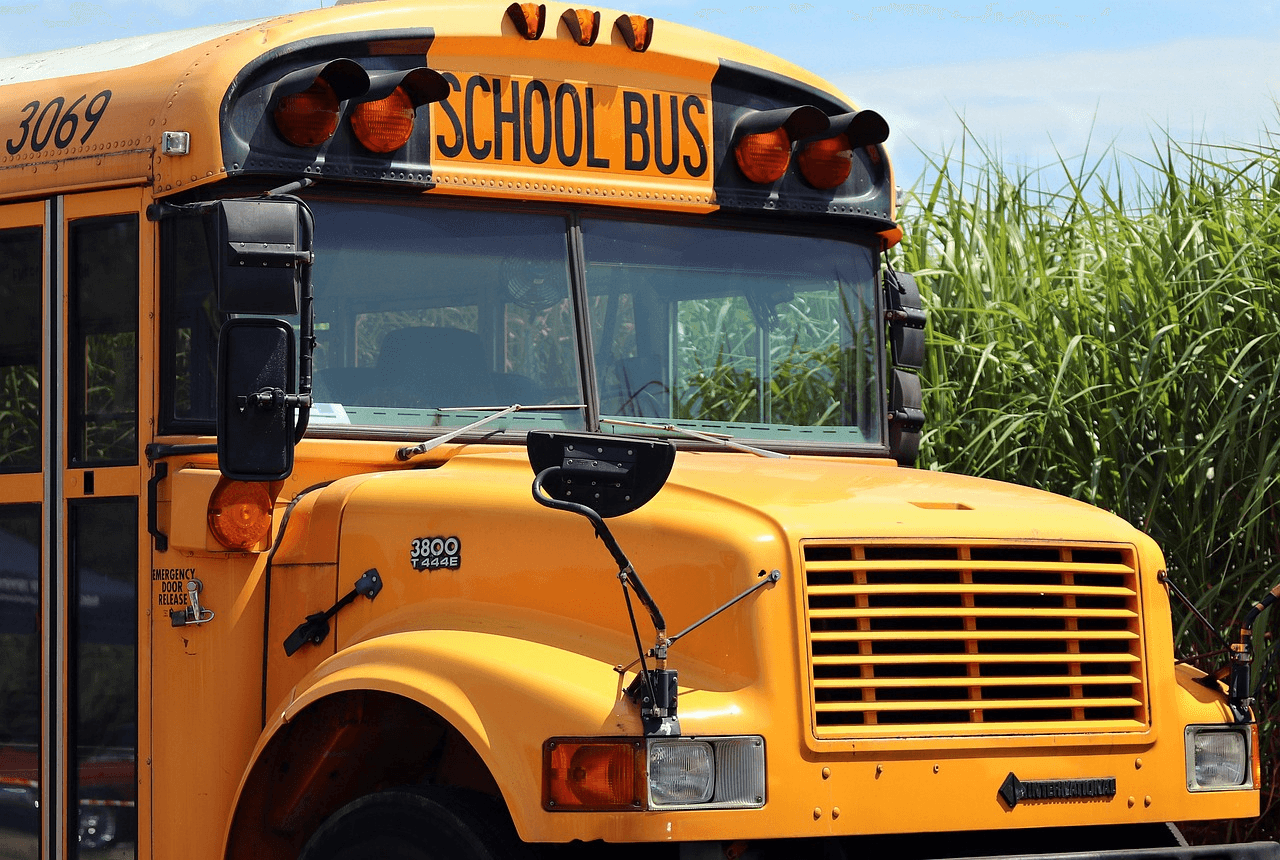

Back to School

College students face serious legal risks with fake IDs, alcohol, and ID misuse under Illinois law.

Do you know what a TVDL is?

Illinois expands TVDL licenses in 2013, allowing foreign nationals without legal status to apply.

To speed or not to speed

New Illinois speeding laws impose Class A or B misdemeanors for driving 26+ mph over the limit.

Concealed Carry Revealed

Learn Illinois concealed carry rules, license requirements, training details, and exceptions for out-of-state residents.

We Will

Wills, trusts, and powers of attorney ensure your wishes and protect heirs.

Protection from the Protection

Illinois may raise liability limits, but reviewing your own insurance is key to protecting your family.

How Work Injuries Work: Step two

Workers’ compensation in Illinois now restricts provider choices with employer PPPs.

The Color Purple

As of 2013, Illinois property owners can use purple paint markings instead of signs to warn against trespassing.

DUI and the HGN field sobriety test- Breaking News!

The Illinois Supreme Court ruled the HGN test admissible in DUI cases, but with major limitations. Learn why this may still help defense lawyers.

Injunction Junction

Orders of Protection carry civil and criminal weight—know your rights and defenses.

Compassionate Use becoming more Compassionate– Illinois Medical Marijuana Updates

Learn about Illinois’ medical cannabis program updates, new qualifying conditions, and how recent legal changes impact patients.

Sobering changes to DUI law at hands of Compassionate Use of Cannabis Pilot Program Act

With medical cannabis legal in Illinois, DUI laws now weigh impairment for valid cardholders.

Warrant Required for Cell Phone Searches

Riley v. California established that warrantless searches of cell phones incident to arrest are unconstitutional.

New Stop Light Camera Rules- 2011

The Illinois Legislature has made new stop light camera rules for 2011. First, in most […] The post New Stop Light Camera Rules- 2011 appeared first on Harter & Schottland.

New Secretary of State Rules for 2011

New Illinois laws impact permits, suspensions, and revocations of driving privileges.

SOS for SOS (Secretary of State)

Suspended or revoked license? Find out how reinstatement works and how legal help can speed up the process.

Court Supervision

Learn how Illinois court supervision works, its benefits, limits, and conditions for avoiding a conviction.

Injured at work

A quick guide on what to do after a work injury, from reporting to benefits.

Off of the Road Vehicle

New Illinois law regulates non-highway vehicles on roads, with strict safety rules and limited exceptions.

Survivors' benefits

Spouses, children, and dependents may receive compensation for accidental work-related deaths in Illinois.

Concealed Carry Revealed 2

Even with a concealed carry license, Illinois law bans firearms in schools, parks, stadiums, and more.

No Longer in Suspense

New Illinois law clarifies repeat DUI-related suspension rules while allowing multiple penalties at once.

One Step Closer to Medical Marijuana

Illinois lawmakers advance a tightly regulated medical marijuana bill, with dispensaries and physician oversight.

41 Ways to Fight a DUI

Experienced DUI lawyers in Lake County fight evidence, tests, and charges to defend your future.

Car Crash Crash Course

Injured in an Illinois car accident? Learn about insurance minimums, medical bills, and personal injury claims.

Cannabis Decriminalization in Illinois?

House Bill 100 seeks to decriminalize small cannabis possession in Illinois with fine-only penalties.

New Law Could Cause Ripples

Starting 2014, Illinois boaters convicted of operating under the influence may lose driving privileges.

Update on Medical Marijuana in Illinois

New Illinois medical cannabis rules cut patient costs, adjust cultivation and dispensary licensing, and open for public comment.

Sexting Statute Created

New Illinois law lets courts supervise minors who share indecent images, imposing counseling or service.

Law during Covid-19

Courts and our office are open during Covid-19. Learn how Harter & Schottland safely continues serving clients with remote and in-office options.

Eavesdropping Law Unconstitutional… For Now

The Illinois Supreme Court ended the state’s ban on public audio recording, but privacy laws still apply.

Reglas Nuevas Para Licencias

Residentes de Illinois sin seguro social podrán solicitar licencias temporales de conducir desde diciembre de 2013.

Medicinal Marijuana Moves Forward

Medical marijuana rules advance in Illinois, with staggered application dates and strict review timelines.

Cars and Cannabis

Starting 2014, Illinois law restricts medical marijuana in vehicles to sealed containers only.

The Load to Carry

New Illinois law raises insurance minimums, but full coverage is key to protecting your family.

School Daze

School zone speed limits in Illinois apply 7 a.m.–4 p.m. on school days when kids are outside.

The Appeal of Appealing your Property Taxes

Learn when to appeal property tax assessments in Lake County and how attorneys can help.

Memorial Day Roadside Safety Checks

Police will increase DUI, seatbelt, speeding, and distracted driving enforcement this Memorial Day.

Driver’s License Suspensions

Traffic tickets may lead to license suspension in Illinois. Know the risks and get legal advice before pleading guilty.

Changes to Theft and Retail Theft Laws

New 2011 Illinois theft laws increase felony limits and expand venue rules for prosecution.

Retail Theft and Civil Liability

Civil liability for retail theft can be costly, but legal help may reduce demands.

How Work Injuries Work: Step One

Timely reporting of workplace injuries is crucial for workers’ compensation benefits.

Temporary Visitor Drivers License (TVDL) Update

New Illinois law lets immigrants without Social Security numbers obtain driver’s licenses starting late 2013.

Can Agents Search My Phone at the Airport?

Learn how the Wanjiku case impacts border searches of cell phones and what travelers should expect when returning to the U.S.

10 Rules to Know to Avoid Getting Pulled over

Learn 10 common but lesser-known Illinois traffic rules to avoid unnecessary police stops.

The Institution

Defense lawyers uphold justice, safeguard rights, and ensure fairness in the criminal justice system for everyone.

Changes to Illinois Traffic Law in 2011

New Illinois laws require seat belts for disabled passengers, stricter speeding penalties, and tougher rules for drivers and cyclists.

Clean your Slate

New Illinois law expands expungement for certain reckless driving charges committed before age 25.

Fighting Drug Cases – Part 1

Harter & Schottland fight drug charges by suppressing evidence from illegal stops, arrests, and searches.

Eviction Description

Learn the five legal steps for eviction in Illinois and how attorneys can help landlords.

Consent to search

Learn how Illinois courts limit police searches under apparent authority and the Fourth Amendment.

Probation in Felony Cases

Illinois law lists serious crimes that require prison time, but defense strategies may reduce charges.

Employer obligation to insure workers

Employers must carry workers’ compensation insurance in Illinois or risk fines, penalties, and even criminal charges.

Roadside Broadside

Illinois checkpoints target impaired driving during holidays; learn how they work and what to expect.

Waiting to Inhale

Despite legalization, Illinois patients may wait until 2015 for medical cannabis as state agencies finalize rules.

The End of the DACA Dream

DACA is ending, but renewals may still be possible. Know your options, deadlines, and next steps for legal protection.